The Art of the Libel Lawsuit: Trump vs. the WSJ

If there’s one arena where President Trump has proven relentless, it’s the battle over public narrative. In The Art of the Deal, he writes: “When people treat me badly or unfairly or try to take advantage of me, my general attitude, all my life, has been to fight back very hard.” That ethos now shapes his approach to the press, where critics are met with expensive lawsuits.

One of his latest targets? The Wall Street Journal.

In July, WSJ published a piece detailing a 2003 birthday album compiled for Epstein’s 50th, which allegedly included a letter bearing Trump’s signature—complete with a hand-drawn outline of a naked woman and the words “Donald” scrawled across a compromising spot.

Trump called the letter “fake,” denied ever writing or drawing it, and promptly sued Rupert Murdoch, the WSJ, its parent companies, and its reporters for libel.

The Lawsuit

A day after the article was published, President Trump filed his complaint, alleging that WSJ defamed him when it published the piece. The complaint accuses each defendant of acting with “actual malice,” ignoring cease-and-desist warnings, and amplifying a fabricated story for maximum reputational harm.

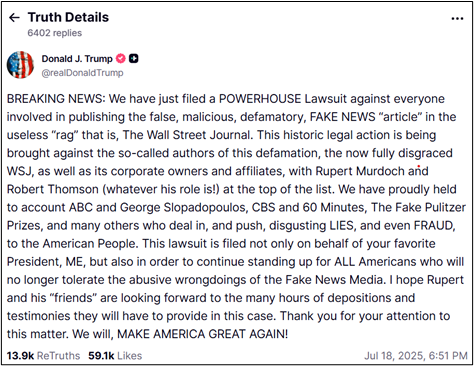

On the day the complaint was filed, President Trump posted on Truth Social and framed this lawsuit as part of his efforts to punish other news outlets, including ABC and CBS.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

But defamation law isn’t a PR strategy to “fight back.” It’s a tort that requires a plaintiff to meet specific legal elements, especially when the plaintiff is both a celebrity and sitting president. To prevail, he’ll need more than quotes from The Art of the Deal and a $20 billion demand for relief.

Defamation Law 101

In New York Times v. Sullivan, the U.S. Supreme Court established a landmark rule: that public officials—and later public figures—must prove actual malice to recover damages, meaning a plaintiff must prove that the defendant published a statement with knowledge or reckless disregard that it was false.[1] This rule imposes a higher evidentiary burden than in other civil cases, requiring would-be plaintiffs to prove actual malice with “clear and convincing” evidence.

The Court explained the rationale for this heightened standard as rooted in the First Amendment’s core commitment to public discourse:

Debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and . . . may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.[2]

Actual malice is a demanding standard, but not impossible to meet. For example, in Harte-Hanks v. Connaughton, the Court found actual malice where a newspaper ignored key sources and failed to interview witnesses who could have disproved its claims.[3] Still, the Court clarified that a failure to investigate, standing alone, does not establish reckless disregard.[4]

Here, Trump’s legal team must show that the WSJ knew or entertained serious doubts about the Epstein letter’s authenticity and published it anyway.

But legal doctrine is only part of the story. The context surrounding this lawsuit suggests a broader playbook, one that may be less about vindicating reputation and more about leveraging litigation as a tool of influence.

Strategic Litigation or Genuine Grievance?

President Trump is the first sitting president to sue media companies while still in office. As both a high-profile public figure and our nation’s highest public official, his legal claims carry symbolic weight and may reflect broader strategy. His growing list of targets suggests a pattern of using litigation not merely to vindicate his reputation, but to exert pressure on various institutions.

According to an amicus brief published by Mindcast AI, this case may be less about defamation and more about “strategic litigation architecture.” The brief describes a pattern of “Coercive Narrative Governance,” in which lawsuits are used to manipulate institutional processes, obstruct congressional oversight, and extract settlements during moments of political vulnerability.

Trump’s lawsuits against other media companies, such as ABC and CBS, support this framing. In both cases, he alleged deceptive editing and false statements, ultimately securing multi-million-dollar settlements. While those outcomes might suggest legal leverage, they didn’t result from courtroom victories on the merits. Strategic framing can’t erase the reality that lawsuits rise or fall on evidence. And the ground beneath Trump’s complaint has already begun to shift.

Where the Case Stands

On September 8, 2025, the House Oversight Committee released photo evidence of Epstein’s 50th birthday book, which includes the same letter that President Trump previously called “nonexistent” and “fake.” The letter was obtained from Epstein’s estate in response to a congressional subpoena, and it matches the WSJ’s description in the article.

Two weeks later, on September 22, the WSJ filed a motion to dismiss, arguing that Trump’s lawsuit should be dismissed for three reasons: (1) the article is true; (2) the article isn’t defamatory; and (3) Trump cannot show actual malice.[5] With the letter now in evidence, it will be hard to prove the letter was fabricated.

The legal battleground shifts from whether the letter exists to whether the WSJ acted with reckless disregard in publishing it—a far more demanding standard under Sullivan. And without evidence of internal doubt or editorial misconduct, the claim of actual malice may struggle to gain traction.

The WSJ Has Strong Arguments

With the Epstein letter now authenticated through congressional subpoena, the WSJ has a strong case that Trump’s claims are deficient on all three fronts: truth, harm, and intent. WSJ’s motion to dismiss frames Trump’s lawsuit as not only legally deficient, but constitutionally dangerous.

As the motion states: “[Trump’s] lawsuit threatens to chill the speech of those who dare publish content that [he] does not like.”[6]

The WSJ argues that the article is factually accurate, non-defamatory, and published without actual malice. They emphasize that the letter was obtained from Epstein’s estate and corroborated by independent sources, including congressional investigators. That alone undermines any claim that the WSJ fabricated or recklessly published false information.

To understand the kind of evidence Trump would need to gather, it’s instructive to look at Dominion v. Fox News Network, where the court confronted similar concerns about press accountability and the limits of protected speech.[7] There, the case involved a trove of evidence—internal emails, deposition testimony, text messages—supporting the claim that Fox knowingly aired false statements about election fraud.

Dominion survived summary judgment and ultimately settled before trial. Although this lawsuit remains at the pleading stage, the comparisons show what courts look for when assessing actual malice.

Trump’s case against the WSJ lacks the kind of evidentiary backbone in Dominion. To win, he would not only have to prove the letter was a fake, but also that the WSJ knew (or should have known) it was fake and ran with it anyway. That means hauling the Epstein estate into court, subpoenaing Ghislaine Maxwell, and somehow showing that the WSJ ignored glaring red flags.

Yikes.

That’s a long shot, and likely not an evidentiary door that Trump wants to open. Besides, the letter has since been released by Congress, and WSJ’s reporting relied on documents obtained from Epstein’s estate. Unlike in Dominion, there’s no current indication of internal doubt, suppressed fact-checking, or editorial manipulation.

This lawsuit becomes less about a disputed document and more about the boundaries of press freedom. If courts begin to entertain defamation claims based on discomfort rather than demonstrable falsehood, the chilling effect could be profound—especially for outlets covering powerful public officials.

Reputation, Retaliation, and the First Amendment

Whether this lawsuit is a genuine attempt to restore reputation or just another entry in Trump’s personal Burn Book, one thing is clear: the courtroom is now the venue for a very public power play. And in this version of The Art of the Deal, reputation isn’t just guarded—it’s litigated.

But if the First Amendment means anything, it’s that the press must be free to investigate, criticize, and publish without fear of retaliation from the powerful.

Joseph A. Tomain, media law scholar and Senior Lecturer at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, says:

All Americans, regardless of political leanings, should stand united in support of robust free speech protections. Strong First Amendment free speech rights protect us all individually. They also protect our democracy by allowing a vibrant and sometimes offensive exchange of ideas, which is critical when it comes to matters of public concern. It would be a mistake to evaluate defamation cases based on one’s agreement or disagreement with the plaintiff’s political positions. What matters is whether the speaker knew what they said was false or entertained serious doubts as to its truth.

Trump’s lawsuit faces steep doctrinal terrain. The First Amendment doesn’t shield falsehoods, but it does protect robust reporting, especially when it involves public officials and matters of public concern. Whether this case survives a motion to dismiss may hinge less on the letter and drawing itself, and more on what the WSJ knew, when they knew it, and how they framed the story.

In the end, the question isn’t just whether the letter is real. It’s whether the law will bend to accommodate reputational discomfort or hold firm in defense of a press that dares to publish what power would prefer to suppress.

[1] See New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 271 (1964); see also Curtis Publ’g Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 (1967) (extending actual malice standard to public figures).

[2] Id. at 285.

[3] See generally Harte-Hanks Communications v. Connaughton, 491 U.S. 657 (1989).

[4] Id. at 688.

[5] Def. Mot. to Dismiss, Trump v. Wall Street Journal, No. 1:25-CV-23232-DPG (S.D. Fla. 2025).

[6] Id. at 21.

[7] Dominion v. Fox News Network, 293 A.3d 1002 (Del. Super. Ct. Mar. 31, 2023).